Harley's Story Chapter 19

Going Where the Wheat Is

ALL HARLEY CHAPTERS

Teresa Holmgren

2/5/20249 min read

Going Where the Wheat Is

From then on, from the day Al died, Charley and the brothers worked as a threesome. Walt kept saying that someone was goin’ into Kearney to get one more worker to replace Al, but it never happened. Maybe, Charley thought, word had got around town that a man died in the wheat harvest, and superstition kept anyone from stepping forward to replace him. It was hard to believe, in these slim-pickins time for work, that anyone would let that stop them. He ended up just figurin’ that Walt didn’t want to spend the gas money to go all that way to pick up one man. Everyone else in the crew seemed to be toleratin’ the work well.

The weather stayed warm during the day, but it was getting cooler at night and they continued to move north. This spread was enormous. Charley guessed that it was at least a thousand acres. He was afraid to ask because he didn’t want anyone to think he was getting tired or that he wanted to quit. It would sound like a little kid in the back of the buggy askin’ his folks, “How much longer ‘til we get there?” He had kept track of the days in a black notebook that Lena had packed in his bag. On the twelfth day, he realized he had not yet written to Lena.

She was probably worried sick and working her way up to bein’ angry. Charley knew he had to write her, but by the time they got back from the field every day, he shaved, got washed up in the creek, and ate dinner, he was all tuckered out. He shoulda written last Sunday afternoon, but he had fallen asleep after the outdoor prayin’ and singin’ service. Some preacher’s son had come over to the camp from the small town nearby to put it on for the men. A good number of them was pretty religious and really appreciated it. But most also took naps afterward. Some of the young ones played horseshoes or cards.

That twelfth day, after dinner, Charley forced himself to stay awake until he got a letter written. He told Lena all about meeting the brothers and about the rail bulls catching the bum they rode in the boxcar with. He told her about Al, of course. He purposely had not thought about it much since it happened, but writing Lena brought it all back. It had truly been the worst thing he had ever gone through, except for the house fire. Charley told Lena, however, that he really had nothing to complain about. He knew that it just as well could have been him lying down back there at the scythe end of the tractor, and Al could have been safe up there under the wheels. He thanked God every day for that.

Charley also described the beautiful golden wheat fields that ran all the way to the horizon in every direction. Charley had never seen an ocean, but he imagined it would be like that - the same in every direction if you was in the middle of it. He was pretty sure Lena would have enjoyed the sunsets, too.

Then, of course, he got around to the main part of his letter which was how much he missed her, missed her face, her hugs, and her pretty blond hair. How much he missed her cookin’ and pies and bread. How the lady who prepared meals for them was a fair cook, but Charley doubted she had ever heard of salt, or pepper for that matter. He told her that what he missed most, except for spoonin’ with her every night, was her chicken ‘n noodles and her lemon poke cake.

Charley didn’t even try to be fancy with his writin’ because he knew he was no match for his wife’s way with words, but he wrote from his heart and he knew Lena would like that. When he was done he had two big pages on both sides. The lines wasn’t so straight, but he made sure Lena could read every word. He looked it over before he put it in the envelope and proudly realized it was the most he had written since his final essay in fifth grade. That would help make up for his first letter to her being written so late, he hoped. Charley told her that he wanted to give her a big squeeze, and that was just what he was gonna do first when he saw her again!

He wrote his Grimes address on the envelope. Lena had already put a stamp on it. For a return address, he was going to have to ask Walt if there was a place Lena could write so Charley could get a letter back from her.

Charley closed his eyes, tipped back his head and tried to picture Lena walking from the house down the short steep drive to the mailbox. This time of year, the milkweed and goldenrod in the ditch would be starting to mature. The monarch butterflies would be thick, and the hawks would be soaring around the front of the property, on the lookout for a ground squirrel snack. Then he remembered; she wasn’t at the farm and the house was gone, but he knew she would be checking the mailbox.

He started wondering about what was going on with Lena’s jobs and with Harley. Charley was savin’ his money and hoped she was doin’ the same. He wrote in the letter that he was getting paid in cash and wasn’t going to take the chance of sending that in a letter. Harley was probably getting itchy for school to start, but first he would have to help Jim harvest his farm and Charley’s farm as well. He knew Harley could do the work, but he wished he could be there to help, too.

Wishin’ was something Charley did a lot of lately. He even wished he could quit wishin’. He was used to making things happen. If he wanted something done, well, he just went and seen that it got done. Shocking wheat wasn’t like that. Nothing ever got done! One enormous field simply blended into the next one. Maybe there was a fence or two, but usually not. Just hundreds and hundreds of acres of grain; and men sweeping across them. On foot, bending over, standing up, and bending over again. Move along, follow the scythe.

Charley hated the sight of that scythe, but there it was in front of him every day. He decided to start thinking that every swipe of that scythe was bringing him a little closer to being home. If he didn’t, these months away from home would maybe kill him. Or at least kill his spirit. He wanted to return to his family as the same ol’ Charley, just with money to build his new home.

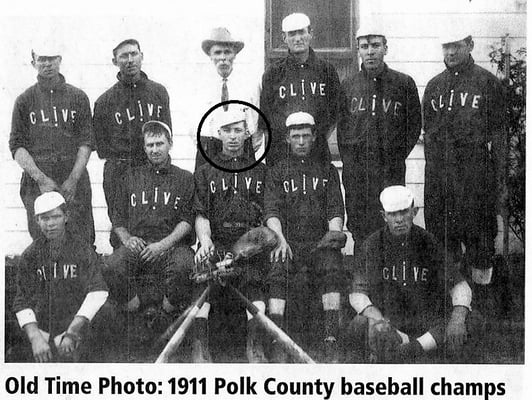

Henry and Mel had the two of them earning money for their family. They was able to save twice as much money as Charley had. He tried to be happy for them. They was helpin’ out their parents, like Harley was helpin’ his folks. All three boys was givin’ up some of their wonderful young years workin’ as hard as grown men. They shoulda been out huntin’ and fishin’ with their friends or playin’ baseball like Charley did when he was their age. He had been the catcher on the Polk County champion baseball team in 1911.

But, these Depression days were not normal times. Very few families, in town or country, were unaffected. Husbands and wives were forced apart depending on where there was work. Children lost their childhood. Many families lost their homes. He had heard of people driving all the way out to California and living in their cars, or in tents by the side of the road. He was living in a tent, but still had no complaints. He had blessings to count and he knew it.

Charley had three squares a day, a place to wash his clothes, and steady pay. There were people unable to feed their families. His family had a huge garden; they would always have food to eat. He just wanted to sit down at the table with Lena and Harley and have a meal together.

Charley realized he was falling asleep, but he wasn’t in his own bed. He had scooted over to the edge of the tent to get the last bit of daylight to write Lena’s letter. He rolled back over and stood up. The brothers were just coming back from the campfire and a card game. They realized Charley was still awake, even upright, and were obviously surprised.

“Hey, old man,” Henry hollered, “What you up so late fer?’

“I been writin’ that letter I told ya about. Don’t want my wife worryin’ no more,” Charley replied.

“Well, ya better let us tuck you in. We got a real long day tomorrow. We gotta pull up this tent before we hit the fields. They’s movin’ us up farther north tomorrow night,” Mel offered.

Charley didn’t know what to say. That was a huge surprise. No one had mentioned that. “That’s a new one to me. When did they decide that?”

“Don’t know,” answered Mel, “but we were tryin’ to decide how long to stay. We done made a lot of money. We been talking about it and think maybe we’ll only stay another two weeks.”

Charley hardly knew what to say, but he knew he didn’t want those boys to leave. They was the best Christians in the camp. No drinkin’ or carousin’ for them. They was darn good clean company for Charley to have, and good workers to boot!

“I don’t see how you could have enough money to really get your folks back on their feet, even with yer two salaries. Ya maybe got enough to make sure your family has a place to live and some food for a month or two, but you kids are gonna have to stick it out here in these fields until winter kicks us out, don’t you know that?” Charley asked.

“That’s what I tol’ the little whelp,” Henry said. He’s the one who wants to go home. Misses his gal and is sick of all this work. I tol’ him he’s jest being a big fat sissy!”

Mel gave Henry a hard shove, sending him to the dirt floor of the tent. “What’d I tell you I was gonna do if you called me a sissy again?” he demanded.

Henry bounced right back up and socked his little brother in the jaw. Men all around them, readying their beds for the night, started jeering. “Fight! Fight! Them two is fixin’ to fight!”

“No, they ain’t!” hollered Charley above the din of the workers’ shouts. “They ain’t fightin, or they’ll be fightin’ me!” He pushed himself between them and grabbed both their shirt fronts and pushed them in opposite directions backwards. They landed in the dirt again and Charley stood there with his arms crossed on his chest. He had not yelled like that for a long time.

“Cut it out! You boys is acting like heathens! Heathens, I tell you!” Then he realized how loud he was being. Lowering his voice, he spoke directly to Henry, “You can’t fight your little brother. I’ll betcha yer mama told you to take care of him. Is that what this is? Huh, it that what this is?”

The boys were still mad, but they were also obviously shamed. Charley was right about their ma. She had told them to watch out for each other, and here they were trying to beat each other up. They still looked pretty steamed at each other, so Charley moved his cot between their cots for the night. They got themselves settled down silently, and Charley told ‘em that their bedtime prayers darn well better include each other and a whole lot about forgiveness. He heard a ‘hrumph’ from each of them, but he knew all would be fine by morning, and it was. Mel probably didn’t like thinking he had to listen to Henry, but he knew Charley was right about them havin’ to stay longer. He didn’t like it at all, but he knew it was gonna be that way.

Takin’ that tent down in the morning reminded Charley of the time a big ol’ circus came to Des Moines, over by Fort Des Moines. Half of the show was watchin’ them put up the giant tent and then take it down again before they left town. The circus had elephants to help with it, but the wheat shockers only had a few horses. Walt kept yelling directions, and they finally got it down and loaded on a long trailer.

They started about six in the morning and finished around ten o’clock. Now they were going to ride another hour in the back of the transport truck, have a lunch of sandwiches, and then work until dark in a new field. Some of the men would stay back in the new camp so they could get the tent put up for sleepin’ in again.

So, this is how it would go. It would be another month or more before Charley could have enough money saved to take home to Lena and Harley. He might as well stay as long as he could. He knew his cousins and neighbors could help him get his house built pretty quick. If they got the outside done, he could finish the inside when winter hit.

The three men shocked wheat until each field was clean. Then they moved on to the next field. Town to town, county to county, Nebraska, Kansas, South Dakota; wherever there was wheat, that’s where they went. Charley and the boys hung in there, going through it all together.