Mable's Story Chapter 44

Steamboat Rock Disaster

ALL MABLE CHAPTERS

Teresa Holmgren

2/9/202421 min read

Steamboat Rock Disaster

There was no way to anticipate it or prepare for it. There was no way to prevent it, or to undo it. When the telephone rang on Sunday morning, August 1st, I answered, but Uncle Albert asked to talk to Mother without even really saying hello to me. I knew there was something wrong. Very wrong.

“Henrietta,” he said, “there’s been a fire. Mother’s house caught on fire last night.”

“Oh no,” Mother shrieked. “A fire? Is there much damage?”

“Henrietta, the house burned completely down. It’s gone. A complete loss,” Albert reported.

“Mother got out, didn’t she?” Mother asked, her voice trembling.

“Yes, she got out. But…”

“But what, Albert? Is she hurt?” Mother was panicking.

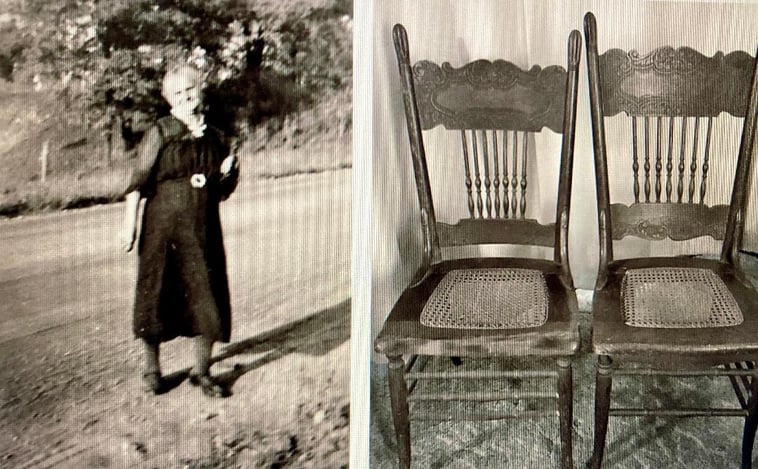

“She got out, but she went back in. She wanted to save the chairs that she and Klaas got as a wedding present.”

“Oh, dear God, Albert, is she hurt? Is she okay? Is she alive?”

Mother waited for what seemed a very long time for the answer to come.

“She was alive, Henrietta. They took her to the hospital in Eldora, but she died shortly after they got her there. She breathed in a lot of smoke and had some bad burns on her legs and arms. She was already old and weak. She was unconscious. She didn’t suffer from the burns, I’m sure of that.”

Then there was a long silence from Mother. Finally, she whispered, “God rest her sweet old soul, Albert. God rest her sweet old soul.” Mother sat down on the hallway bench and started to cry. She handed me the receiver.

“Uncle Albert, I don’t think Mother can talk anymore right now. What is happening?”

“I am going to come to Des Moines this afternoon and pick up you and your mother, Mable. You’ll be staying with us. The funeral parlor in Eldora is going to handle the arrangements. We have called the pastor at Bertha’s church. He’ll announce it during the service this morning, but this town is so small, everyone already knows. I expect the ladies will start bringing over the cakes and casseroles this afternoon, or tomorrow for sure. Aunt Helen is going to stay home and take care of all that business. There will be a lot of visitors at our house. Everyone loved your grandmother.”

This was more information that I could remember all at once, but I said, “I’ll let Mother know. She may want to call you back, if that’s okay?”

“Tell her I am leaving in just a little bit. Aunt Helen will be here, if she wants to call her. Help your mother. You will have to pack a few things and plan to stay for a few days, until after the services. I’m going to hang up now. Be a good girl, like you always are, until I get there.” He hung up.

I went over and sat on the bench. I put my arm around Mother’s shoulder. She suddenly turned and grabbed me in a big hug. I started crying, too, and we just sat there, hugging and crying.

First my father, and now my grandmother. I was trying not to think selfishly, but it was hard. My poor mother. She had lost her mother and her husband in the same year. She was not taking this well. I had always thought of her as a strong woman, but in my arms right now, she felt drained and frail.

Uncle Albert arrived in record time. It was about 2 o’clock. His old Ford must have flown. We were ready. Mother was anxious to get there, and I think it was because she was having a very hard time believing it had really happened. She was almost in shock. We learned about that in first aid during health class at North. I had tried to make sure she was getting lots of iced tea to drink and even had her lie down in her bed for a bit before Uncle Albert arrived. She said she felt dizzy. She was okay by the time he got there, so Uncle Albert put our suitcases in the car and we prepared to drive off.

Suddenly, Mother hollered, “Wait!”

“Wait for what?” I asked.

“Mable, run back inside the house, write a note to Burnie’s mother and put it in their mailbox. I don’t want to bother them with this now, it will just hold us up from leaving, but I want them to know where we have gone so they don’t worry.”

That was just like Mother. I guess she was going to be okay after all. She was still her thoughtful, considerate self. Telling Burnie had not even occurred to me. I was too busy taking care of Mother and getting ready to leave. I ran into the house, wrote the note, and put it in their post box as instructed. I hopped back in the car and we sped away. Uncle Albert was not wasting any time.

The drive to Steamboat Rock was full of all the details of my grandmother’s death. It was a horrible fire, and no one could tell how it started. It was Saturday night, so she may have been filling some of the oil lamps she used and spilled some fuel, which then got accidentally ignited. She didn’t really trust electricity, so she very seldom used it, even though her house had been wired for several years. Grandma was pretty old-fashioned.

Her neighbors said that she ran out of the house, screaming in German. They came outside and saw the fire. A couple of them ran back into the house with her to help save some of her things and throw them into the front yard. After about two trips in, it became too hot and dangerous to go back, but again, Grandma yelled something in German and disappeared around the back of the house. The neighbor across the street from her speaks German, and thought she hollered something about her “wedding chairs.” They tried to follow and stop her, but by the time they got around to the back, Grandma was already inside her flaming house again.

It was about that time that a few of the volunteer firemen showed up. They had buckets with them and were ready to start a line of men from the well in the side yard, but the house was almost totally in flames. The neighbors were screaming for Grandma to come out. What came flying out the back door was a wooden chair. Then a second chair came sailing out. The front of the seat of that chair was on fire, so one of the neighbors threw some dirt on it. Then Grandma came out and fell face down on the back steps. Fortunately, she was unconscious from that time on.

Her arms and legs were badly burned. Her shawl and her skirt had caught fire. Uncle Albert knew those chairs had been at the kitchen table. She may have caught her clothes on fire from the tablecloth when she grabbed the chairs. Running back and forth to the back door most likely fanned the flames on her clothes, but she paid that no mind. Her intent had been obvious; she had to save her treasured chairs. Well, they were saved, but my precious Grandma Von Dornum was gone.

Slowly, as Mother and I absorbed this horrible story from Uncle Albert, it all became more real to me. I knew it was true. No more pretending that maybe it was a bad dream or something. So, I asked about Grandma’s hair. I have no idea what possessed me to do that, but it just popped into my head. My grandmother had beautiful, thick, long hair. That was pretty unusual for a woman her age. Most old women had thin graying hair, but not Grandma. She mostly wore it up, braided and twisted around the top of her head like a pile of halos. On Saturday nights, she usually took it down and washed it, so it would be nice again for church on Sunday. She never wore it down in public, just around the house on Saturday nights.

My relief was immense when Uncle Albert told me that she had her hair up in braids still and it was not down! He said he figured that if she was filling the oil lamps, she would not have taken it down yet. It would have been in the way as she went about doing that task; it was almost down to her waist.

By the time he finished telling us all the details, we were in Hubbard, with only about ten miles left to go to Eldora. I wanted to get there, but I didn’t want to get there. I also didn’t know what to expect, but I knew the first stop would be at the funeral parlor, because Mother insisted on that.

I said I would wait in the car, and Mother said, “Of course you will wait in the car. They are not going to let a child in there to see her before she is prepared for viewing.”

That meant the embalmer had not done his job yet, but Mother didn’t care. She had to see. That was it. No debating it. I was very happy to sit in the car. The only dead person I had ever seen was my father. Back then, I prayed that the rest of my family would live for a very long time; I really did not want to go to another funeral for many more years, and here my dear grandmother was gone just a few months after my dad. I started crying again.

Mother turned around from the front seat and looked sternly at me, saying, “Pull yourself together, Mable. Your grandmother was a Christian woman and is in a better place. She is having no pain. She is with your father. It is perfect in Heaven. Do not cry. Rejoice.” Then she added, “And if you must cry, please don’t cry in my presence. It just tempts me to cry. I have done my crying, and I’d like to keep it that way. From now on, I shall be rejoicing.”

She certainly was German. Tough and resilient. Her mourning period had been longer for Dad, she spent about three days crying. I still cried sometimes when I missed him, like when I wanted to tell him something about baseball, or at graduation. I even thought about him after winning the mile swim. I didn’t tell Mother that. I wondered if she thought about him now and then. I would never know, because even if I came right out and asked her, I knew for certain that she wouldn’t want to talk about it.

We pulled up to the front of the funeral parlor. They had not been in business too many years. People used to have wakes in their homes. Funerals had always been held in churches. Lately, more people were using funeral parlors for wakes, but still having the funerals at the churches. Mother and Uncle Albert got out. Uncle Albert went up to the front door with Mother, and then they went inside. I could see Uncle Albert standing inside for the whole time. Mother must have gone somewhere to see Grandma, but Uncle Albert stayed by the front door.

After about fifteen minutes, Mother came back and they walked slowly back to the car. They were visiting quietly, and even paused on the sidewalk to finish their conversation before they got to the car. Mother was dabbing her eyes a little with her sleeve, but Uncle Albert did not reach out to comfort her. In fact, she even stepped away a bit.

When they got to the car, they were done talking and Mother was done dabbing. We drove silently to Steamboat Rock. The quickest way to get there was on a little road that went past, or really around, Pine Lake. There were a few picnic tables under some trees, but most of the woods around the lake were too thick for a picnic. You could barely see through them, they were so close together. That lake was good fishing. I remembered fishing there for what seemed to me to be hundreds of times with Dad before we moved to Des Moines. There were some men working on a huge stone wall by the dam going into the Iowa River.

As we drove into Steamboat Rock, we went past the little dirt road that went down to the banks of the Iowa River. There was a viewing point there where you could stand and see the actual rock that looked like a steamboat. Mostly it looked like the top of a steamboat, the tall part where the captain would stand and steer the boat. I always thought that rock was pretty nifty. When I moved to Des Moines and tried to tell my new sixth grade friends about it, they were not as impressed as I thought they should be. Then I realized they were comparing it to places like the Iowa State Fair and Riverview Park. That’s when I learned what a sheltered life I had led for the first eleven years of my life. It was a good eleven years though. I grew up in Steamboat Rock, Iowa, learning to appreciate the simple things in life and knowing that I was loved.

Grandma’s house had been in the northeast corner of town. We drove there first. Mother wanted to see what was left. It was the house where Klaas and Bertha lived when they sold the farm, after all the kids were grown. Uncle Albert stopped the car and we just sat there for a few minutes. None of us spoke. I wanted to ask some questions, but I knew it was not the right time. Finally, Mother got out. She stood in the front yard, and then walked to the back yard. I stayed in the car again, and so did my uncle. We both sensed that Mother wanted to be alone on this walk. As I was sitting there, I noticed that Grandma’s beautiful floribunda rose bush was totally gone. It had been consumed by that house fire. The hundreds of blooms that were there this time of year, right next to the front porch, were gone forever. All that was left in that lot were the tall singed trees, most of the brick chimney, and the smoldering pile of ashes that used to be the house.

I could see the top of Mother’s head over the smoky pile. She was looking at the hill of ashes, broken glass, and bricks. Then she would look down for a minute, almost like she was praying. It was sobering and educational for me. This had to be part of mourning the loss of her mother. My heart felt so heavy, but I knew I was not going to cry again right now, as I saw Mother heading back around to the front of the house.

She was walking rather briskly back to the car. She walked right up to the car door, swung it open and announced, “You know, Albert, there is one good thing I remembered. Do you recall two Christmases ago when you and Aunt Helen showed up with that cedar chest of our mother’s? She wanted me to have it and you brought it down to Des Moines? You know, it has all her quilts in it. Every single one. She didn’t keep even one up here for herself. They weren’t in this fire and I am so glad about that. I’d rather have my mother than those quilts, but now I don’t. I’m just happy to have those beautiful quilts. Those will be yours someday, Mable. You will have her quilts, like you have her name.”

My name is Mable Bertha Woodrow Hall. Grandma’s name was Bertha. I was proud to have her name and I would be thrilled to have her quilts . . .someday. However, Mother was right. I’d rather have my grandma.

Now we would be going over to Aunt Helen and Uncle Albert’s house. Friends would be waiting there. Mother would not cry. I probably would, the minute I saw Aunt Helen. I would have to head back to the bedroom though, because Mother had made it plain that she did not want to see any more of my tears. I was a strong, resilient German-in-training, and I needed to act like one. Dealing with tragedy was relatively new to me, so I wasn’t very good at it. These older people just seemed to know how to do whatever had to be done and then keep going.

Little Miss Mable Hall. I was an only child and had led a rather sheltered life. I wasn’t like mother, who lost a little brother in his teens, whose deaf mother didn’t speak English, or whose father died when she was a teenager. She became strong at a young age. I had experienced very few struggles in my life. Probably the hardest thing I had ever had to do, before Dad died, was to make new friends when we moved to Des Moines. Even that wasn’t really difficult, with Burnie living right next door.

Aunt Helen greeted us at the door. As I peered into the kitchen, which was right off the porch through which we entered, I saw the old wood stove she still used. There were two ladies sitting at the kitchen table, which was laden with rolls, salads, cakes, and pies. I smelled the savory aroma of beef stew, or perhaps it was pot roast. It was Sunday, after all, so whatever meal was going to be served tonight was going to be substantial.

“Oh, Henrietta, this is so awful. And happening so soon after we lost John Henry. I am so sorry,” Aunt Helen offered, shaking her head and hugging Mother.

“It’s good to be back with family, Helen. Thank you so much for everything you are doing,” murmured Mother, hugging her sister-in-law back.

Uncle Albert was bringing in our suitcases, so I asked him, “Do you need any help? Is there anything left in the car?”

He replied, “No, dear. You just stay with the ladies. I’m doing fine out there. You and your mother really didn’t bring that much.”

I followed Mother into the parlor. The house was just one story and much smaller than ours. They had a son and a daughter, who were grown with families of their own. This small three-bedroom house just fit their family. Most of the houses in town were very modest. Eldora had some really large and lovely homes, but not Steamboat Rock. Aunt Helen and Uncle Albert’s children and grandchildren lived in town, but way over on the west side, on the banks of the Iowa River. I really shouldn’t say “way over,” because Steamboat Rock is only about ten blocks wide. Until Mother and Dad moved to Des Moines, the Von Dornums were a very close-knit family.

There were two more women in the parlor. Aunt Helen introduced them to me and to Mother as ladies from the church, Theresa Thierauf and her daughter, Rosemarie. They were there to pray. That was one difference between small rural towns and large cities like Des Moines. In Des Moines, people go to church to pray. In Steamboat Rock, people would know you so personally that they felt comfortable coming to your house to pray.

Rosemarie, who looked to be about thirty years old, said, “We are about to start another prayer. If you’d like, please join us.”

Her mother started praying, “Dear Heavenly Father, we thank you for this family and for their faith in you. We thank you for this day of worship, and we thank you for receiving our beloved Bertha into your loving arms today. We know she is surrounded by your angels and resting with your son, Jesus. Bless this family in their grief, for they surely loved Bertha and will miss her greatly.”

Rosemarie picked up where the older Mrs. Thierauf left off, adding to the prayer with, “And, dear Lord of all, please bless the firemen who tried to help Bertha, and the neighbors to ran to help her, too. Give peace to the doctor and nurse who cared for Bertha at the hospital. Let their hearts feel your love and purpose for them. They are your hands here on this earth. And most especially, Lord, we thank you for Bertha having her human fragilities healed up there with you in Heaven. We want to shout hosannas for Bertha being able to hear all your angels singing and all those heavenly harps playing. We shall sorely miss her, dear Father, and pray you will wipe away our tears.”

She continued on with more supplication, “Do not let us dwell on our sorrow, gracious God, but help us rejoice with you that Bertha has come home; that she is now with her son Wiard and with her husband Klaas. Make us feel the joy and delight that you feel with her inside your golden gates. There is no greater happiness than to know Bertha is with you, her Creator and Master, as we pray these prayers. Please accept our eternal gratefulness and appreciation. In the name of your son, and our Savior, Jesus Christ, we pray. Amen.”

I opened one eye and looked sideways at Mother. She was not crying, but there was a tear falling off her cheek. It fell on her bosom. She did not wipe her face, but she wiped her bosom. She looked over at me. We were seated on a settee, next to each other. She reached over and took my hand in hers.

She looked right into my eyes and said softly, “These are such good people, Mable. We are at home here. These folks loved Bertha. I do believe they are going to miss her as much as we are. This whole town loved her, you know.”

I had to respond but was not sure what to say. I tried, “I’m glad we are here, too. I liked that prayer, Mother. These are really nice folks.” Mother smiled a little and patted my hand, so that must have been the right thing to say. I was just not used to all this sadness. I was going to have to pass through this experience and learn from it.

This was very different than when Dad died. All his friends were there and such, but there was more banter and joking, not so much religion. I did feel more comfort now, just hearing about Grandma Von Dornum being in Heaven with Dad. Real comfort. The church women left with their husbands, who had been out in the backyard during the praying

We ate a huge dinner, which was good because Mother and I had not eaten lunch. The table was so heavy with food that I thought it would collapse. I think they were going to have to save those pies and cakes for the lunch after the funeral, because I was so full, I could not possibly have eaten a single bite of dessert. Several old friends of the family stayed for dinner, but there was plenty of food left over for meals in the next few days.

Mother and I were getting pretty tired and Aunt Helen could tell. “You two girls need to hop into bed. I put a warm bowl of water on the dresser, with a couple of towels and washcloths so you can wash up quick. We will need to go by the church early tomorrow and talk to Pastor Biddle about the funeral program and music. I sure did love what Mrs. Thierauf prayed about Bertha being able to hear in Heaven.”

I never thought about that. I wondered if I would be able to hear perfectly when I got to Heaven.

“Well, goodnight and God bless,” she said as she waved us to the back bedroom that had been her daughter’s room. “Sleep as well as you can.”

Mother and I got ready for bed pretty silently. I had a bunch of questions that I wanted to ask, but I knew this was not the right time. Mother looked very thoughtful and that was always a good sign she needed to be left alone. We were sleeping in the same double bed, so that meant being alone would be difficult unless I was extremely quiet. I saw a Bible on the nightstand, so I washed up, put on my night gown, and slipped into bed with the Bible. Mother got into bed and rolled over, turned away from me.

“Goodnight, darling daughter,” she whispered. It sounded so soft and sweet. It was like she was imagining that her own mother was saying goodnight to her. Tears started to gather in my eyes, but I wiped them on the sleeve of my gown.

“Goodnight, dear Mother. I’m going to read the Bible and say my prayers, then I will turn out the lamp, okay?”

“That’s fine, Mable. You are such a good girl. I am so proud of you.” There was that feeling again. It was like she was saying the things she would want her Mother to say to her tonight. Sometimes she had told me that I had too big of an imagination. I don’t think I was imagining this. I truly felt it in my heart. I know my mother’s heart was breaking, and I could do nothing to help her; except maybe just be her darling daughter.

“I love you, Mother.”

I love you, too, Mable.”

I did not read or pray very long. I was exhausted.

Monday at the funeral parlor and at the church was no fun. I didn’t really expect it to be, but the detais of a funeral and burial were too much. It was good that Dad had paid a funeral insurance policy for Grandma Von Dornum. All the expenses would be covered, so there would be no extra financial strain on Mother or Uncle Albert. The insurance money on the house would come later, at which time my mother and her brother would have to decide what to do with the burned down house and the lot upon which it sat.

The wake was going to be Tuesday night, and the funeral was Wednesday morning. We would be back in Des Moines late Wednesday night or Thursday. I would have so much to tell Burnie, I wouldn’t even know where to start.

The rest of Monday and most of Tuesday was spent visiting with old friends of Mother’s, eating cake and pie and salad. I also ate lots of sliced ham and deviled eggs. It seemed like I was gaining five pounds a day. I started to worry about fitting into my fall clothes for college. Mother seemed to be surviving on cookies and iced tea. Every time I looked, someone was bringing her a glass of tea and a plate of cookies.

The wake was held at the Eldora funeral parlor on Tuesday evening. The funeral was in the German Baptist church in Steamboat Rock on Wednesday morning. Some of the hymns were sung in German and some in English. The same thing applied to the prayers and the songs, some were in German and some in English. I had never been to a service like that. It was only the second funeral in my life, though. All I had to compare it to was Dad’s funeral.

The pastor spoke in English; I appreciated that. I wanted to hear and understand what he had to say about Grandma. He spoke simply, but beautifully, about how so many people loved my grandmother. Nearly every store in Steamboat Rock and Eldora was closed for the morning. She had worked all those years at the dry goods store, so she knew everything about everyone in town, but she was kind and she never gossiped. As well as being friendly and fair, she was hard-working. Grandmother went out of her way to help people, including all sorts of neighbors when they needed assistance. She was usually the first one there when a family in Steamboat Rock had a crisis. Even though she could not hear, she made up for that with a sense of what was exactly the right thing to do in most every situation. I never knew all that about her. I just knew that I loved her. It was like a warm comforting hug from hundreds of people, to hear that the entire town loved and respected her.

The townsfolks of Steamboat Rock were so kind to us the whole time we were there. Mother wanted to stay a few more days, as she said she had to talk over insurance and other matters with Uncle Albert, the bankers, and some other people. I wanted to get home to Burnie; we only had a few more weeks to be neighbors before I left for Iowa City and he headed off to Purdue.

A few more days turned into two weeks. I began to wonder if we were ever going back to Des Moines. Oh, I enjoyed going swimming and fishing at Pine Lake and visiting with my cousins, but I was ready to go home days before Mother finally made her announcement, “Mable, I’m going to move back to Steamboat Rock.”

“What?”

“I’m going to make Steamboat Rock my home again. Your father is gone, you are leaving for college, and there is really no reason for me to stay in Des Moines. It’s far enough away from here that it gets hard for me to see the rest of my family. They are what I have left now, along with you, and I want to live here again.”

I was stunned. Somehow, I thought to ask, “Exactly how is this going to work, Mother? When are you going to move? Where are you going to live?”

Mother had it all planned. “I will live with Uncle Albert and Aunt Helen until the new house is built. We will sell our house in Des Moines and with the insurance money from the fire, there will be enough money to build a new house where the old house was. Your Uncle Albert and his friends are putting together a big crew to help build the house, and I hope to move in by mid-December; we’ll have a new home for Christmas.”

“What about me and the University? How is that going to work?” I could not conceal the doubt and concern in my voice. Mother put her arm gently around me.

“It will work out fine, darling daughter,” she assured me. “We will be in the house in Des Moines until you leave for school. It will most likely be Thanksgiving before the new house is done.”

I’m sure I still looked puzzled, because she continued, “When you pack up your things for Iowa City in August, you can just pack up everything else in your room. We will move them to Steamboat Rock and everything will be in your new room when you come home for Christmas.”

I just looked at her. She seemed to finally realize that this decision was a complete surprise to me. I had not heard her speak about this at all since Grandma Von Dornum’s funeral.

“I suppose you are wondering when I decided all of this and why I didn’t talk to you about it?” she finally asked. She answered herself. “I decided this at Grandma’s funeral. All the folks in this town loved her and they kept asking about your father, and about you going off to college. They didn’t want me to be all alone in that big house way down in Des Moines. I realized then that Steamboat Rock is home. I told Uncle Albert that I thought I should talk with you about it, but you know, he’s a man, and he thinks those decisions are best left to the adults. He spoke with the insurance man and the bankers and all of a sudden there was a plan.”

I understood. Mother had always loved her family and had not been able to see them more often than a few times a year. She truly would be alone in Des Moines. “I understand, Mother,” I managed with a little smile. “I really love this little town, too. I know it’s home to you.”

Mother looked relieved and her shoulders relaxed with a deep sigh. “I know it will be a lot different for you. Thank you so much for understanding, Mable.”

So, we left for Des Moines the next day. Mother and I had a long list of things to do to get me ready for the University of Iowa. Also, I could finally get back to Burnie, after our sudden departure. There was so much to tell him.